History of neuroscience: Julien Jean Cesar Legallois

The idea that different parts of the nervous system are specialized for specific functions has been a pervasive concept in brain science since ancient times, perhaps best exemplified by the belief---dating back to the 4th century CE---that the four cavities of the brain known as the ventricles each were responsible for a different function, e.g. perception in the twolateral ventricles, cognition in the third ventricle, and memory in the fourth ventricle. By the early 1800s, however, there was still no definitive experimental evidence linking a particular function to a circumscribed area of the brain.

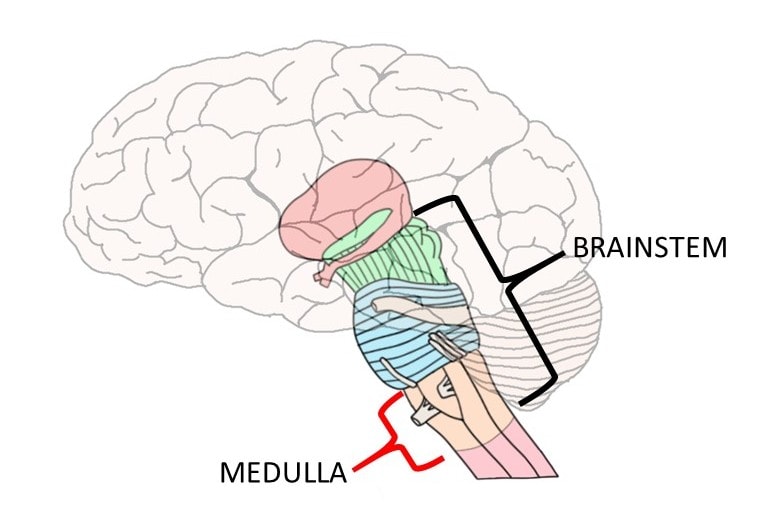

Image showing the medulla oblongata, the region of the brainstem that Legallois found was essential to respiration.

This changed with Julien Jean Cesar Legallois, a young French physician who was driven to identify the parts of the brain and body that were essential for maintaining life. The thinking at the time was that the heart and brain were both integral to life, but there was some debate about where the life-sustaining centers in the brain were located. Some, for example, considered the cerebellum to be the organ that controlled vital functions like heartbeat and respiration. Research conducted in the second half of the 18th century by the French physician Antione Charles de Lorry, however, had suggested that the area of the brain most critical to life was found in the upper spinal cord. Legallois would take Lorry's research a step further by conducting a series of gruesome experiments with rabbits that would help him to specifically pinpoint the center of vital functions in the brain.

Before detailing these experiments, it's important to mention that Legallois' studies were done at a time when the ethical treatment of animals in research---and indeed ethics in research at all---were not given much thought. Legallois was a vivisectionist, meaning that he performed surgery on living animals in his experiments. Legallois' work would not be likely to be approved by a university or research institution today, and indeed when you read Legallois' own impassive descriptions of his grisly experiments they sound like something a budding serial killer might have dreamed up before he moved on to human victims. But this was a different time, when thoughts about animal welfare were not as well formulated as they are now---and Legallois was far from the only vivisectionist of his day. Indeed, a great deal of our current neuroscience knowledge was developed using experimental methods we would consider unjustifiably cruel today.

Legallois' method of exploring the centers of vital functions in the brain primarily involved the decapitation of rabbits. Legallois observed that after a decapitation made at certain levels of the brainstem, the headless body of a rabbit could still continue to breathe and "survive" for some time (up to five and a half hours according to Legallois). Decapitation further down the brainstem, however, would cause respiration to cease immediately. This observation was in agreement with Lorry's. Legallois then set out to isolate the particular part of the brainstem where these respiratory functions were located.

To do this, Legallois opened the skull of a young rabbit (while the rabbit was still alive), and began to remove portions of the brain---slice by slice. He found that he could remove all of the cerebrum and cerebellum and much of the brainstem, and respiration would continue. But, when he reached a particular location in the medulla oblongata---at the point of origin for the vagus nerve---respiration stopped. Thus, Legallois surmised that respiration did not depend on the whole brain but on one circumscribed area of the medulla. He concluded that the "primary seat of life" was in the medulla, not the cerebellum or cerebrum.

Legallois published the details of his seminal experiment in 1812. We now consider the medulla to be a critical area for the control of respiration as well as the regulation of heart rate, and the region is often considered to be a center of vital functions in the nervous system. Indeed, Legallois was influential in establishing the hypothesis that the brain is involved in the regulation of heart rate as well (prior hypotheses had emphasized the ability of the heart to act alone---without the influence of the brain). While Legallois was not the first to hypothesize that vital functions are localized to the medulla (he was preceded by Lorry), he was the first to provide clear experimental evidence linking the medulla to such functions, and he greatly refined Lorry's estimation of where the vital centers were located. In the process, Legallois gave us our first clear evidence that linked a function to a localized area of the brain.

Cheung T. 2013. Limits of Life and Death: Legallois's Decapitation Experiments. Journal of the History of Biology. 46: 283-313.

Finger, S. 1994. Origins of Neuroscience. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

For more about the medulla oblongata's role in vital functions, read this article: Know your brain - Medulla oblongata