Ghrelin and the Omnipresence of Food

It really is difficult to travel a mile in this country without being exposed to something trying to entice you to eat. Billboards, mini-marts, and restaurants have saturated our environment with visual cues that remind us of the importance of feeding. When at home the television, radio, or internet can be helpful if one has a tendency to forget the necessity of food—especially that of the fried, dripping, or cheesy variety. The advertisers behind all of these reminders are hoping that when you encounter them, your stomach will be coincidentally flooding your hypothalamus with ghrelin.

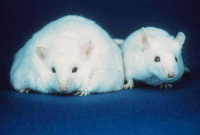

Ghrelin is a hormone produced by the gut. You may have heard of ghrelin’s counterpart: leptin, a hormone that is integral in letting the brain know you have had enough to eat. This is important, as can be seen by looking at mice with a genetic mutation that results in an inability to produce leptin:

Ghrelin seems to play the role opposite to leptin’s, it lets you know that the stomach is getting empty and it is time to eat. Ghrelin levels are highest before a meal and lowest afterwards. When ghrelin levels are raised experimentally, people are found to eat more than those administered a placebo.

Ghrelin receptors (and leptin receptors) are especially prevalent in the hypothalamus, but a recent neuroimaging experiment shows that ghrelin may have a much more widespread effect on the brain.

A study published this week in Cell Metabolism describes the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to investigate ghrelin-related brain activation. Participants were scanned while looking at food and nonfood images. Some of the subjects received an infusion of ghrelin before the fMRI.

The ghrelin injection resulted in an increase in brain activation in areas associated with evaluating the hedonic value of a stimulus—the “reward centers” of the brain, along with a large network that includes visual and memory areas. These are some of the same regions thought to be responsible for drug-seeking and other types of addictive behavior.

Thus, high levels of ghrelin may make our advertisement-laden and food-available environment a dangerous one in which to live. But the hormone may also represent a plausible method for treating obesity. Vaccines that raise an immune response against ghrelin have been shown to be effective in reducing weight gain in rats. Their use with humans is currently being investigated.

Until (and if) they are found to be effective it is best just to try to ignore the constant urgings all around us to “eat, eat, eat”.