Know your brain: Meninges

Where are the meninges?

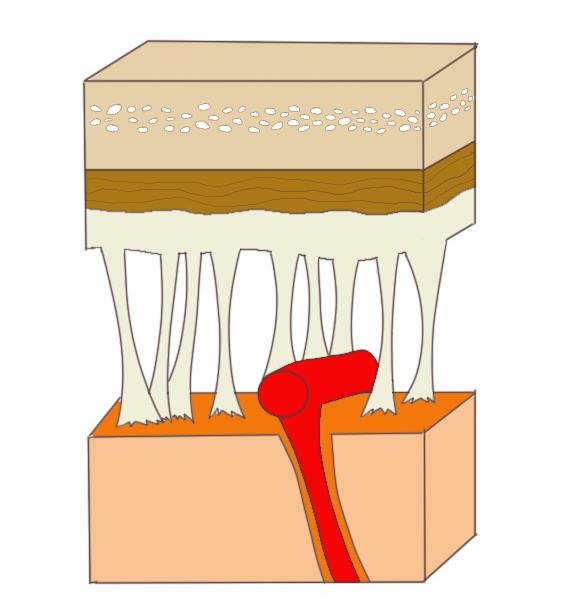

The term meninges comes from the Greek for "membrane" and refers to the three membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord. The membrane layers (discussed in detail below) from the outside in are the: dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater. Their positioning around the brain can be seen in the image to the right.

What are the meninges and what do they do?

The brain is soft and mushy, and without structural support it would not be able to maintain its normal shape. In fact, a brain taken out of the head and not properly suspended (e.g., in saline solution) can tear simply due to the effects of gravity. While the bone of the skull and spine provide most of the safeguarding and structural support for the central nervous system (CNS), alone it isn't quite enough to fully protect the CNS. The meninges help to anchor the CNS in place to keep, for example, the brain from moving around within the skull. They also contain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which acts as a cushion for the brain and provides a solution in which the brain is suspended, allowing it to preserve its shape.

The outermost layer of the meninges is the dura mater, which literally means "hard mother." The dura is thick and tough; one side of it attaches to the skull and the other adheres to the next meningeal layer, the arachnoid mater. The dura provides the brain and spinal cord with an extra protective layer, helps to keep the CNS from being jostled around by fastening it to the skull or vertebral column, and supplies a complex system of veinous drainage through which blood can leave the brain.

The arachnoid gets its name because it has the consistency and appearance of a spider web. It is much less substantial than the dura, and stretches like a cobweb between the dura and pia mater. By connecting the pia to the dura, the arachnoid helps to keep the brain in place in the skull. Between the arachnoid and the pia there is also an area known as the subarachnoid space, which is filled with CSF. The arachnoid serves as an additional barrier to isolate the CNS from the rest of the body, acting in a manner similar to the blood-brain barrier by keeping fluids, toxins, etc. out of the brain.

The pia mater is another thin layer, but unlike the arachnoid it closely follows all of the contours (e.g., gyri and sulci) of the brain. Thus, instead of a cobweb, it forms a tight membrane around the brain and spinal cord. The pia acts as a barrier and also aids in the production of CSF.

These three layers are similar in structure and function around both the spinal cord and brain, but there are a few differences. While there is not normally a space between the dura and skull, there is one between the dura of the spinal cord and the bone of the vertebral column. It is known as epidural space, and analgesics and anasthesia are sometimes injected here. Also, the dura of the spinal cord and its accompanying arachnoid layer extend several vertebrae below the end of the cord. This creates a CSF-filled area called the lumbar cistern where there is no spinal cord present. The lack of the presence of the cord makes the lumbar cistern a good place to sample CSF when necessary because one doesn't have to worry about damaging the spinal cord with a needle puncture. Thus, the lumbar cistern is the site where CSF is aspirated in a lumbar puncture, also known as a spinal tap.

There are a number of things that can go wrong with the meninges. Due to the large numbers of blood vessels that travel through these membranes, many problems are vascular in nature. For example, blood (e.g., due to damage caused by trauma) can collect in spaces between the layers of the meninges, creating a hematoma that can put pressure on the brain as it expands. Also, the meninges are susceptible to infection, most commonly due to viruses or bacteria. Such an infection can cause meningitis, which is characterized by an inflammation of the meninges. Because of the importance of the meninges in protecting the brain and maintaining normal brain function, meningitis can pose a serious threat to the brain and potentially be life-threatening.

Reference:

Patel N, Kirmi O. Anatomy and imaging of the normal meninges. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2009 Dec;30(6):559-64. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2009.08.006. PMID: 20099639.