Know Your Brain: Default Mode Network

Where is the default mode network?

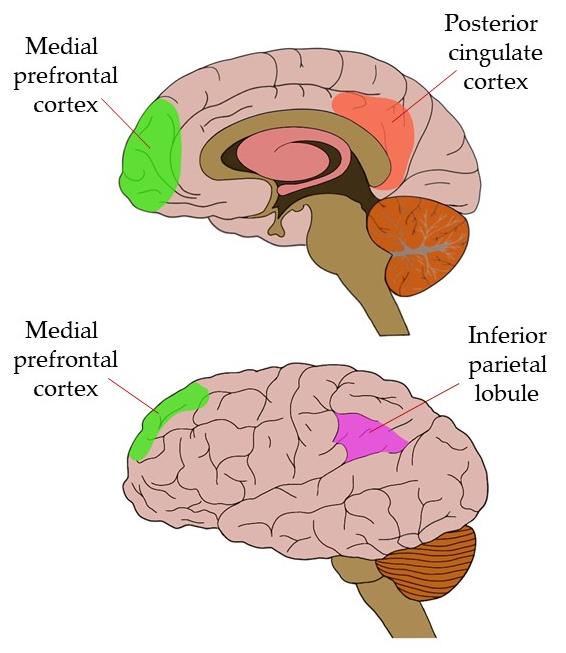

The default mode network (sometimes simply called the default network) refers to an interconnected group of brain structures that are hypothesized to be part of a functional system. The default network is a relatively recent concept, and because of this there is not a complete consensus on which brain regions should be included in a definition of it. Regardless, structures that are generally considered part of the default mode network include the medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and the inferior parietal lobule. Some other structures that may be considered part of the network are the middle temporal lobe and the precuneus.

What is the default mode network and what does it do?

The concept of a default mode network was developed after researchers inadvertently noticed surprising levels of brain activity in experimental participants who were supposed to be "at rest"—in other words they were not engaged in a specific mental task, but just resting quietly (often with their eyes closed). Although the idea that the brain is constantly active (even when we aren't engaged in a distinct mental activity) was clearly expressed by Hans Berger in the 1930s, it wasn't until the 1970s that brain researcher David Ingvar began to accumulate data showing that cerebral blood flow (a general measurement of brain activity) during resting states varied according to specific patterns; for example, he observed high levels of activity in the frontal lobes of participants at rest.

As neuroimaging methods became more accurate, data continued to accumulate that suggested activity during resting states followed a certain pattern. These data were easy to come by because in many neuroimaging studies, asking participants to rest in a quiet state is considered the control condition. In the early 2000s, Raichle, Gusnard, and colleagues published a series of articles that attempted to specifically define the areas of the brain that were most active during these rest states. It was in one of these publications that they used the term default mode to refer to this resting activity, phraseology which led to the brain areas that exhibited default mode activity being considered part of the default mode network.

Thus, the default mode network is a group of brain regions that seem to show lower levels of activity when we are engaged in a particular task such as paying attention, but higher levels of activity when we are awake and not involved in any specific mental exercise. It is during these times that we might be daydreaming, recalling memories, envisioning the future, monitoring the environment, thinking about the intentions of others, and so on—all things that we often do when we find ourselves just "thinking" without any explicit goal of thinking in mind. Additionally, recent research has begun to detect links between activity in the default mode network and mental disorders such as depression and schizophrenia (more on this below). Furthermore, therapies like meditation have received attention for influencing activity in the default mode network, suggesting this may be part of their mechanism for improving well-being.

The concept of a default mode network is not without controversy. There are some who argue it is difficult to define resting wakefulness as constituting a unique state of activity, as energy consumption during this state is similar to energy consumption during other waking states. Others have asserted that it is unclear what the patterns of activity during these resting states mean, and thus what the functional importance of the connections between the regions in the default mode network really are.

These caveats are worth keeping in mind when you come across research on the default mode network, as—especially due to its relationship with meditation—it is becoming a frequently-used term in popular neuroscience descriptions of brain activity. The idea of a default mode network, however, is not universally accepted; even those who endorse the idea concede there still is a lot of work left to do to figure out the network's exact functions. Regardless, at the very least the concept of a default mode network has sparked interest in understanding what the brain is doing when it is not involved in a specific task, and this line of research may help us to gain a more comprehensive understanding of brain function.

The default mode network in disorders and other psychiatric conditions

As interest in the default mode network has increased, so have explorations of the role of the network in disorders and other types of atypical cognitive function. While most hypotheses about the role of the default mode network in these conditions are still relatively preliminary, in this section I will discuss potential contributions from the default mode network to several psychiatric and neurological conditions.

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease patients display overall reductions in brain activity that correlate with the symptoms of the disorder (e.g., memory loss). Interestingly, these patterns of decreased brain activity overlap with areas of the default mode network. Structures of the default mode network are also prominently affected by the neurodegeneration that occurs in Alzheimer's disease. There is even some evidence that Alzheimer's disease pathology begins to appear in the default mode network before symptoms of the disease become apparent, which has led to the hypothesis that dysfunction in the default mode network is key to the progression of Alzheimer's disease.

Schizophrenia

Some research suggests that the default mode network is overactive in individuals with schizophrenia. One hypothesis is that people with schizophrenia may have a more difficult time shifting their thought patterns away from the internally-focused thinking characteristic of the default mode network. Additionally, overactivity in the default mode network might reflect a difficulty in distinguishing between thoughts and sensory perceptions, which could contribute to hallucinatory experiences.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Studies have found that people with ADHD have atypical connectivity in the default mode network, which might be associated with distractibility. It has been hypothesized that the increased activity in the default mode network may interfere with the function of networks involved in attention and cognitive control.

Depression

One of the common cognitive characteristics of depression is a tendency to ruminate, or mentally dwell on the negative aspects of one's life. This type of maladaptive rumination is thought to be not only a tendency of the depressed mind, but also a habit that perpetuates depression by focusing primarily on negatives and ignoring the positives in life. Studies have found activity in the default mode network to be increased during maladaptive rumination, which might exacerbate depressive symptoms.

The default mode network has been implicated in a number of other conditions as well, such as autism, bipolar disorder, PTSD, and others. It's important to emphasize again, however, that much of the research into the default mode network and psychiatric disorders is in its preliminary stages, and it's unclear what role the brain network might play in these conditions. In most cases of psychiatric disorders, it's likely that multiple brain networks contribute to the appearance of symptoms, so it's improbable that the default mode network alone can explain any of these conditions.

Reference (in addition to linked text above):

Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain's default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008 Mar;1124:1-38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. PMID: 18400922.

Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Ford JM. Default mode network activity and connectivity in psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:49-76. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143049. Epub 2012 Jan 6. PMID: 22224834.