History of neuroscience: Ramon y Cajal

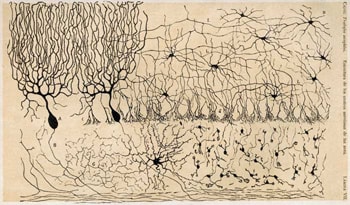

Cajal's depiction of neurons in the cerebellum.

Although many consider him now to be the "father of modern neuroscience," when Santiago Ramon y Cajal (1852-1934) was a boy he dreamed of one day being an artist. His father, who was otherwise very nurturing to Cajal's intellectual development, discouraged the expression of Cajal's artistic aspirations. He saw art as a fruitless endeavor, and he was nothing if not a pragmatist. Nevertheless, Cajal found ways to surreptitiously obtain art supplies (for example, by scraping paint from walls to extract color from it) and continued to practice his art in secrecy.

Fortunately for the neuroscientific community, Cajal also heeded his father's advice and ended up attending medical school. After graduating, Cajal had a prodigious impact on brain science. Cajal became interested in neuroscience at a time (the late 1800s) when microscopy had developed enough to allow for the observation of the cellular components of the brain. Technology didn't yet exist, however, to allow one to take pictures of what one saw through the microscope. Thus, scientists would often have to resort to drawing the structures they observed. Because of this, Cajal's artistic talents would not go to waste.

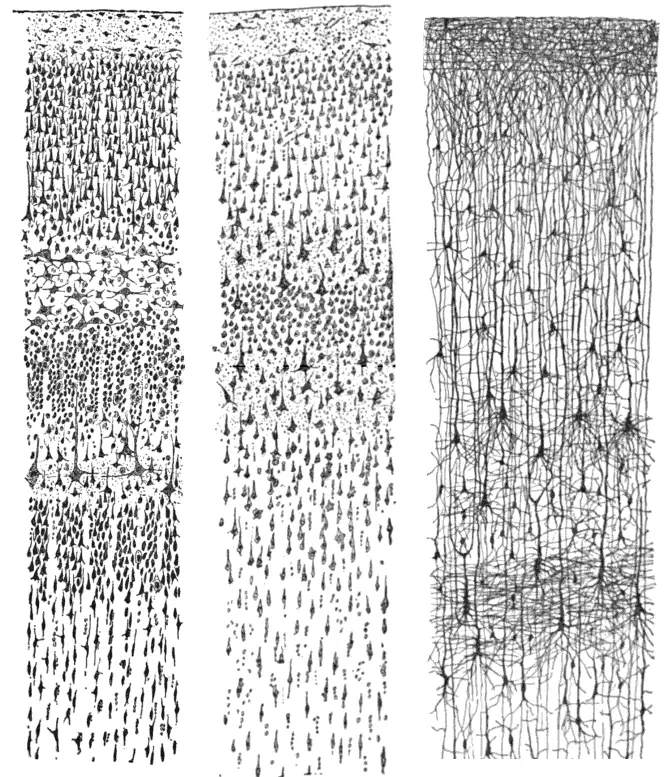

Cajal's representation of the layers of the cerebral cortex.

Cajal embarked upon his professional scientific career in 1884 when he took a Professor of Anatomy position at the University of Valencia in Spain. At the time, the widely held view of the brain was that it was made up of a single network of nerve fibers that were all physically connected to one another. In other words, the nerves of the brain were thought to make up one big, continuous nerve net. In 1873, however, Camillo Golgi had developed a new stain (a stain is simply something added to cells for microscopy that allows the cells or their structures to be seen) that allowed nerve cells to be visualized more clearly under a microscope. When the processes of neurons could be seen with better resolution using the Golgi stain, some began to suggest that nerve cells were just that: individual cells that were not actually connected to each other. Enter Ramon y Cajal.

Although Golgi's staining method made it easier to see neurons, it still didn't allow one to definitively determine if neurons were uninterrupted or separate entities. Ramon y Cajal, however, solved this problem by using thicker sections of tissue, applying a darker stain, and staining embryological neurons that were not yet myelinated (the Golgi stain does not work well with myelinated neurons). With these improvements, Cajal was able to show that the brain is made up of neurons that are separated from one another by microscopic gaps (later called synapses by Sir Charles Scott Sherrington). This finding led Cajal to develop what became known as the neuron doctrine. The doctrine suggested that neurons are discrete units, and that signals are propagated by being passed from neuron to neuron (the mechanism for this wasn't known at the time, but was later determined to be neurotransmission). Cajal won the Nobel Prize (along with Golgi) for this work in 1906.

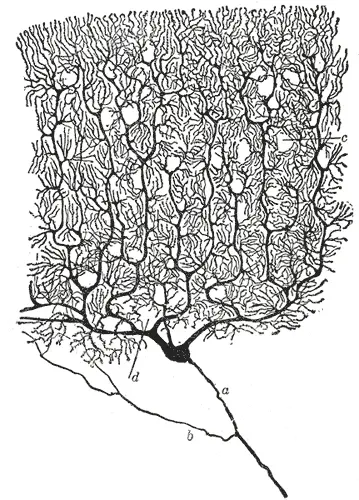

A Purkinje cell, drawn by Cajal.

Cajal made many other valuable contributions to neuroscience. For example, he demonstrated that axons grow from extensions of neurons called growth cones. But he also left behind a vast collection of meticulous and beautiful artwork that captures our understanding of the brain in his time. Cajal represents an overlap between science and art that seems to have been lost over the years, probably because our technology no longer makes it a necessity. Although it is no longer necessary to sketch out observations made with a microscope, however, it could be argued there was some benefit gained from the time Cajal spent meticulously recreating on paper what he saw through his microscope. It may have--based on the degree of familiarity with the cells it would have engendered--allowed him to form a better understanding of neurons. And that comprehension may have been what prepared his mind to make the discoveries that influence neuroscience to this day.

López-Muñoz, F., Boya, J., & Alamo, C. (2006). Neuron theory, the cornerstone of neuroscience, on the centenary of the Nobel Prize award to Santiago Ramón y Cajal Brain Research Bulletin, 70 (4-6), 391-405 DOI: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.07.010